ANDREW STEVEN – CUMBERLAND

OH, CUMBERLAND

YOUR CATS HAVE RUN OFF WITH MY LIMBS

TO PAINT THE DOGS, NOW THEY’LL BLEND IN

AND TWICE AND FAST BENEATH MY SKIN

OH, THE WILDS

THE WILDS ARE WHERE WE BEGIN

OH, CHILD

THE WILDS CALL FOR THICKER SKIN

OH, CUMBERLAND

YOUR GRASS IS FREE UNLIKE OUR SINS

GREEN STILL THAN PARKING LOTS

OR EIGHTEEN DEEP NO SPOTS TO MARK

OH, THE WILDS

THE WILDS ARE WHERE WE BEGIN

OH, CHILD

THE WILDS CALL FOR THICKER SKIN

OH, RUN, RUN FROM THE FLOCKS

OH, RUN, RUN TOWARD THE DOCKS

RUN, RUN, RUN MY CHILD, FROM THE DOGS

OR THEY’LL BITE YOU DOWN A NOTCH

OH, THE WILDS

THE WILDS ARE WHERE WE BEGIN

OH, CHILD

THE WILDS CALL FOR THICKER SKIN

ASHES & OATH – THIRTEEN MILES

From the ice to the trees

With a brisk evening breeze

The street lights, we follow them home

As we walk down the tracks

In the blistering black

towards drinking to love notes we wrote

Which were read in the stalls

Between gas station walls

As the deaf sing their fears to the blind

Up dark hills we crawled

As our fingers thawed

From the warmth of the stars in our eyes

So here is to whatever lies ahead

To uncertainties, challenges, and conversations

I’ve longed to be that person in the end

The one who goes through drive-thrus backward

for the hell of it

From stars to the sea

You were carried within me

In a red bag that was burnt on both ends

We would gaze through the night

In a moonlit delight

As our hands danced across varied skin

Which protected the pain

From a warm upward rain

So the war wasn’t lost to envy

We cling to the past

Onto feelings we’ve stashed

Though our hearts decided to stay

So here is to whatever lies ahead

To uncertainties, challenges, and conversations

We’ll get there, love, I know, it may take a bit

But thirteen miles don’t feel so long

when you’re with me walking it

Thirteen miles don’t feel so long

when it’s you I’m walking with

D. OBE – CIRCLES

THEY SAID WE WERE SPRINGIN LIKE A SLINKY

RUNNIN DOWN LIKE WATERFALLS

IF YOU PITCH A BALL IT’LL MISS ME

HOME RUN SWING, I WAS ALWAYS GONE

RIDING DOWN FROM SIXTH DOIN 60

HIT A BUMP NOW WE’RE FLYING SOUTH

GOD DAMN, SHE LOOKS LIKE A CITY

ALL THAT CLASS NOW IT’S OPEN MOUTH

GOT A SEASON PASS, BRING HER WITH ME

HITTIN HILLS LIKE ITS KENNYWOOD

NO WE’RE BACK TO MATH LOOKIN LITTY

TURTLE NECK AND SOME WATER SHOES

I SPILLED JUICEY JUICE ON THIS THRIFTY

OUT 50 CENTS,NOW It’S IN THE WASH

WITH THE PRADA GLASSES AND SPIFFIES

NO NICE THINGS, ALWAYS TOSS EM OUT

I’M RUNNIN IN CIRCLES

I’M RUNNIN IN CIRCLEs

i’M RUNNIN IN

i’M RUNNIN IN

i’M RUNNIN IN

anD RUNNIN IN

anD RUNNIN IN

anD RUNNIN IN

anD RUNNIN IN

WOKE UP AND LOST MY WALLET

ATE SOME MONEY SO I’M TELLIN NOW

GOT A HOLE DEEP IN MY POCKET

JUST ANOTHER WAY TO SAY I’M BALLIN OUT

BURNIN MONEY LIKE THE CHRONIC

PRETTY SURE MY CHANGE FELL INSIDE THE COUCH

LIFT UP A CUSHION AND TOSSED IT

FOUND SOME WITCHES AND A WARDROBE, WOW

FLEW FROM A SWING AND A GROOVED THROUGH THE TREES

SALTY LIKE SEA ON AN AFTERNOON BREEZE

ESPECIALLY WHEN I FORGOT TO LET GO

IT’S AN IMPORTANT REMINDER, I THOUGHT YOU SHOULD KNOW

ALWAYS LET GO

ALWAYS LET

RUNNIN AGAIN ROUND THE AFTERNOON BEND

FAILED ALL MY TESTS PLAYIN MAGIC INSTEAD

TAPPIN THE LAND LIKE HER BACK AND FORTH HAND

FALLIN ASLEEP, REST MY HEAD IN THE SAND

AWOKEN BY FOOTSTEPS, NO COOKIES FOR MAN

LOCK ALL THE DOORS, WINDOWS OPEN FOR FRIENDS

JUST MAKE SURE THAT YOU CLOSE THEM AGAIN

BECAUSE I’LL FORGET

I’M RUNNIN IN CIRCLES

I’M RUNNIN IN CIRCLEs

i’M RUNNIN IN

i’M RUNNIN IN

i’M RUNNIN IN

anD RUNNIN IN

anD RUNNIN IN

anD RUNNIN IN

anD RUNNIN IN

IN A ROOM FULL OF MEN

Even years after some young boys from the Parisian suburbs ran around the streets of Lisses and Evry, parkour remains a male-dominated discipline, even in age.

It has always seemed odd to me that gymnastics, a discipline with similar physical attributes could be female dominant, yet the female crossover from gymnastics to parkour is few and far between. Is there something inherently different about these two disciplines that attracts one and not the other, or is there something within the parkour community keeping women away?

In every city I have ever visited for parkour, men are the majority. Even in Mexico City, an urban jungle filled with 21.5 million inhabitants and home to one of the largest parkour communities on the planet, there is no exception. While Mexico also has one of the highest numbers of women parkour practitioners, there is still an enormous gap between male and female practitioners.

Mexico also suffers from a long history of machismo or aggressive masculine pride. Male entitlement, superiority complex, sexism, and misogyny are ingrained within Mexico’s culture and continue to be reinforced through machismo. Even after decades of fighting, it seems as if there are still places that the feminist movement and ideology of equality haven’t been able to breakthrough.

Mexico also suffers from a long history of machismo or aggressive masculine pride. Male entitlement, superiority complex, sexism, and misogyny are ingrained within Mexico’s culture and continue to be reinforced through machismo. Even after decades of fighting, it seems as if there are still places that the feminist movement and ideology of equality haven’t been able to breakthrough.

A few years ago, I was invited to Mexico’s “Reunion de Traceuses” where I learned about the impact of machismo on parkour’s culture in Mexico. Many women were unable to attend the event without being accompanied by a male companion for “their safety” while traveling or training, and because of this, the event openly invited men so that more women were capable of attending. But to my surprise, men didn’t jump at the chance to take advantage of the offer, and the event saw the highest number of female attendees alongside an exact 1:1 female to male ratio. Event organizers Skaylet SaLiinaz and Karla Castellanos González used the men’s attendance to spread the ideology of equality and equity, making certain that there was space for women to train with women and women to train without the unwanted opinions, advice, and input from men. What I saw was mutual understanding and respect between all.

Over the past three years, I’ve seen my fair share of male superiority and sexism within parkour in Mexico – from the use of derogatory, sexist language around women (and in general), to unwanted advice and advances while training. I wanted to know whether machismo had its space within parkour culture and whether it was one of the potential factors in the amount of female participation within the discipline.

So what is it like being a woman in a national event full of men within a country with an overly masculine culture?

For Angelica, it’s complicated, and the same macho culture from the outside world seems to exist within her parkour space. “Here in Mexico, they call me a whore because I train around many other men,” Angelica says, “and many of them try to flirt with me or make sexual advances, so I need to create my own space and raise my own spirit to work through it.”

Unlike the others, a young mother to one of the jam’s participants, Dhalia, feels “safe” within the male-dominated training environment. She believes that “many young people are changing their minds,” and with them, the old ideologies of inequality. While she still sees many older people clinging to hateful ideas and actions, she sees hope in the younger generation.

Thamara Monroy, a long-time practitioner from Mexico City, tries to look at both sides and sees something different. “Many women that I know haven’t had the chance to be around 50 or 100 men, being able to do what they want while being respected,” she says. She believes that through parkour, she has surrounded herself with a particular type of men. “I feel very supported by many of them,” she says, and coming to this event, she was “welcomed with an amount of love that I had almost forgotten because I wasn’t here.” And for the times that she didn’t feel respected because a man was giving her unwanted advice or started moving in a space where she was already moving, when they were confronted, she was met with honest apologies.

While some machismo influence within Mexico’s parkour scene seems to linger, something within parkour also creates a space where it is more difficult for inequality to exist. But how much machismo is actually present within parkour here, and what does it look like?

Thamara sees a lot of it within competitive nature and our desire to thoughtlessly outperform others and ourselves. “I see it in both men and women,” she adds, “And we start to say things like, ‘I need to be better!’ But what does that mean?” The problem is that many here don’t have an honest answer, and more than being better, they’re looking for notoriety from their peers. “It’s a very masculine way to grow for younger boys. It’s like you need hit them, and push them, and be kind of mean with them for them to become stronger – and I see a lot of that in parkour,” Thamara adds. She doesn’t see it as much between people but how we treat ourselves. Even if we’re injured, or something hurts, we’ll decide to push through the pain and continue anyway. “It’s the way that we learn,” Thamara says, “and I say we because I also feel my masculine side learning that. It’s a way for us to give value to ourselves by showing that we are strong.” However, strength comes in many different shapes, and she feels that parkour tends to take the most masculine one. “This battle and this confrontation – it’s nice to have that because sometimes we use that kind of strength, but there are also more subtle strengths.” Like being capable of saying I don’t want to do something if I don’t feel it, but there tends to be an opposition to that form of strength that is seen as a weakness, and while she feels that it stems from a cultural dialogue, she hears it a lot within parkour as well. “I hear it when we don’t do some jump: ‘Yeah because I’m a pussy…’” And it’s words like those coming from our mouths that may turn women away from wanting to take part in the community or at all.

After talking with many women within the jam space, one thing seemed to be certain: men providing unwanted advice was constant. “Many men here try to help or offer advice without asking,” says Herme Castro, a young practitioner from Mexico City. “Many of them also think that because I’m a girl, I’m not capable of doing something, which is why they come to help in the first place,” she adds. Just as men want the space to work through things, women want the same, and this issue isn’t an issue that is exclusive to women, but one seen throughout our practice. If you are someone who enjoys sharing knowledge or helping others, instead of just providing them with what you believe they need, why not ask if they’re interested in your help? By asking, not only are you making an honest effort to connect with an individual as an equal, but you are also showing them and the space you share the respect they deserve.

“It’s not black and white,” Thamara says, feeling that too much weight is given to one perspective, as the opposing side and everything in between is undervalued or ignored entirely. Just because the issues exist doesn’t mean that every man is at fault. There are men doing beautiful things, not just for parkour but in general, and it’s important that those things are recognized. And once they are, then what? What needs to change for the current and future women of parkour to create a more conducive environment for them?

For Herme, it’s important that women step up to inspire other women to participate, but also to empower women who are already training through exhibitions, tutorials, and free classes. While Dhalia hasn’t experienced or seen the same struggles within parkour, she has in everyday life and believes that women need to learn to say no. “The time is now,” she says, “for us, it was forbidden” as Mexico’s conservative and macho culture didn’t allow the space for that no to exist. And now? Dhalia says, “We are learning to say no.”

As for Thamara, she has heard the question, “What do you girls need to feel better here?” far too many times over the years. “It’s not like telling you to not say bad words in front of me,” she says, and for her, that’s like an incomplete recipe. “I believe the feminine side of parkour has a lot to give to the masculine side,” Thamara adds, “If we take these masculine and feminine energies, what can we create from them? We already see a lot of the masculine side here, but the feminine side is missing.” And this idea is something that she intends to work on. “Come back in a year, and you’ll see,” she says half-jokingly with a big smile on her face.

Parkour Earth Petitions 2024 Olympic Inclusion

Parkour Earth (PKE) have sent a letter to the IOC officially petitioning FIG’s attempt at parkour inclusion in the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris.

The official petition requests the IOC to formally recognize and accept parkour’s currently governing structures, and work directly with the parkour community through PKE to meet Olympic inclusion guidelines as an autonomous discipline.

“We haven’t had any response yet, so I’m anticipating we won’t hear anything until after the IOC decision is made, if at all,” says Damien Puddle, Chief Executive Officer (NZL). “The IOC doesn’t like controversy,” Damien explains, “So if they did start having discussions with us, I imagine they would be asking us to collaborate with FIG in some way.”

This isn’t the first time that parkour’s Olympic inclusion has been denied. The IOC Executive Board rejected a similar proposal for the gymnastics inclusion of parkour in the Tokyo 2020 games back in 2017, and due to current IOC policy and the current quota of 10,500 competing athletes, it’s unlikely that the proposal will be accepted.

While we await a decision on parkour’s Paris 2024 inclusion status, Parkour Earth urges the community to continue supporting grassroots practices and communities. “Work towards developing a national body if none exist in your country, “Damien says, “Consider joining Parkour Earth and helping us to ensure an international body for parkour meets the needs of the community at large.” There may be other suggestions that Parkour Earth would advise, but those will ultimately depend on the IOC’s decision.

Parkour’s 2024 Olympic inclusion will be determined at a meeting on December 7th, 2020.

At the time of writing, PKE has had no reply, formal or otherwise, from the IOC. Subsequently, nobody from the IOC was available to comment.

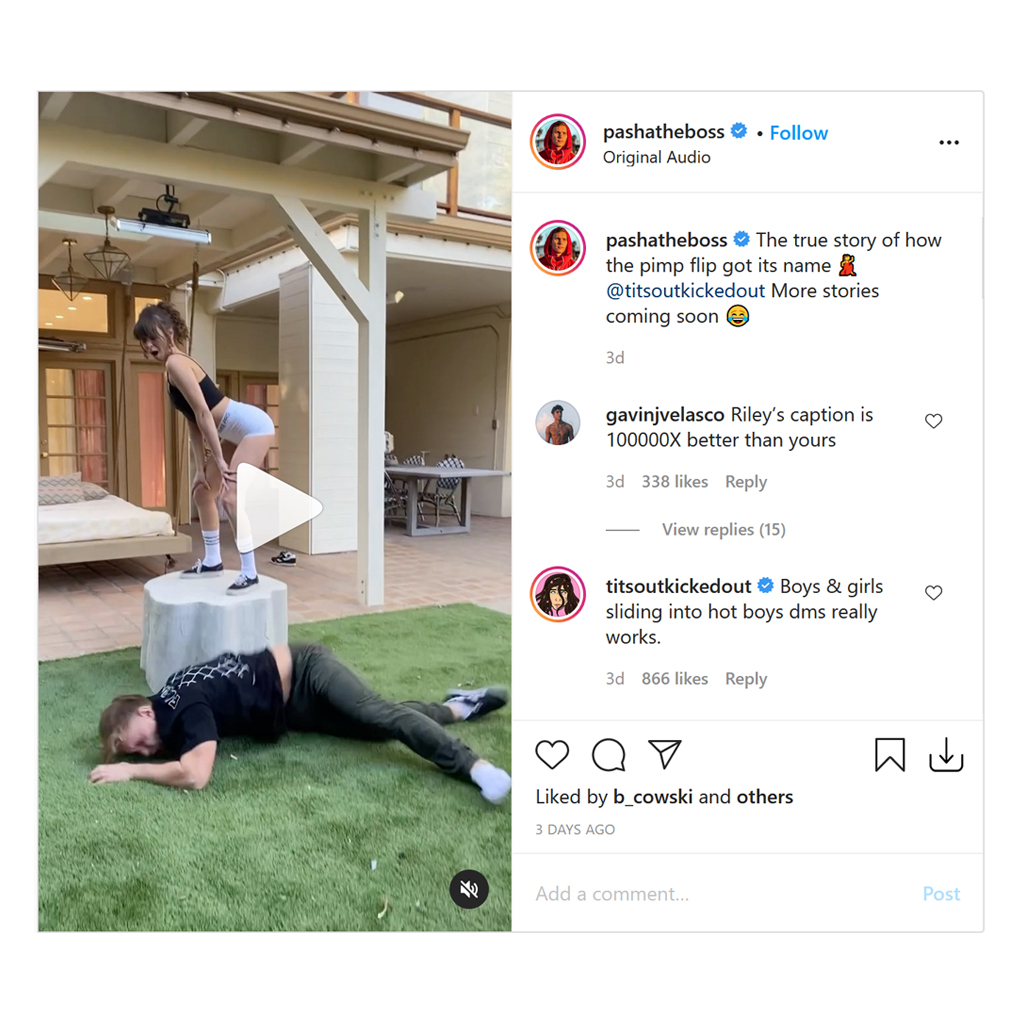

Pasha Petkuns and Riley Reid Post Stirs Controversy

Controversy has arisen within the parkour community after Pasha Petkuns released a collaborative Instagram post with successful adult entertainer and porn actress, Ashley Mathews, better known as Riley Reid.

The post was released Monday, December 7, 2020, by both parties after Riley Reid had reached out to Pasha with an offer to collaborate. The video itself portrays two consenting adults, one of which is successful in the sex industry, acting out a sexually implied scene utilizing movement. The actions have been labeled by women in and outside of parkour both as “objectifying” and “empowering,” and the reactions between the two followings differing drastically. Many women within parkour have presented their discomfort and the broader potential implications on sexism within the discipline/sport, while those interacting with Riley and in similar communities are seeing the side of “a dominant and independent woman in control of want she wants”.

While Riley Reid has no association with parkour, nor is representing female parkour athletes, it does bring up concerns for those who have experienced sexism within discipline/sport. The post was followed by a barrage of concern, anger, and calls to action for the community to unfollow Pasha in protest. Stories and posts by Hazal Nehir, Lorena Abreu, and Callum Powell have been circulating throughout the community in opposition to the post’s content, but it’s not the post alone that poses an issue.

Recently, there has been a surge of women bringing up the issues and experiences of sexism within parkour, and this post seems to be adding fuel to the fire. “At its best, the video is just cringe. At its worst, it’s contributing to a bigger problem. The reason this discussion has become so big isn’t because of the video itself,” Lorena Abreu explains. “Posts like this, in the context of our sport, make many women like me feel uncomfortable and/or disrespected. Many women have already been subjected to varying degrees of harassment and sexism in our sport. Some actually have some quite shocking stories. So posts like this really hit a nerve and contribute to a culture that we are frankly exhausted from dealing with,” Lorena adds.

However, it’s not just the women complaining. Callum Tips no.555 is dedicated to the men who are unwilling to listen. “There are still a lot of people that are reluctant to see it from the perspective of those affected by Pasha’s recent controversy, as well as numerous, increasingly ubiquitous examples of similar viral-seeking-trash content perpetuating the same effect,” says Callum Powell, “I think people should make the effort to understanding those making points against the post rather than shouting about censorship and freedom of expression, which, granted, are very important to keep one’s guard up about.”

While many are upset at the recent post, this isn’t the first time that Pasha, as well as a plethora of other prominent athletes, posted something controversial. It’s even led to a few imitators following suit. Pasha posted another collaborative video with Hannah Stocking, who has a much larger following than Riley or Pasha, back in July. The video displays Pasha doing a front flip before Hannah removes her clothing and jumps onto him.

While parkour is a male-dominant activity, men are not the only ones involved and that is something that needs to be considered. “Listen to people’s concerns about how this sort of content affects young women wanting to start parkour or at various stages of their practice. It shouldn’t be a norm that women should feel their only merit is their appearance when practicing a sport or posting their clips online,” Callum proclaims. And we should be concerned. Over the past few years, there has been a growing trend of sexist comments flooding the profiles of practicing women. “I responded to almost all of them,” Lorena explains, “They were generally like 12-16 years old and looked like they’d been training around a year. So content like Pasha’s post contributes to an attitude that we so do not need to keep fostering in our sport.”

Drew Taylor said it best, “We cannot control the content on social media that is associated with the sport. Therefore the parkour community needs to be clear on what will not receive support, backing, or respect.” And the women are singing a similar tune. “If we want to avoid parkour from becoming a toxic, sexist culture, we need to reject those attitudes and communicate that it’s not welcome,” Lorena says.

Pasha, who considers himself a movement artist, began his road to fame within parkour, but has also moved beyond the sport to become a well-known internet sensation. “I’m just a kid who likes to play,” Pasha tells us, “I’m happy that we have a community and a lot of people supporting me, but I care about my close friends more than I care about my followers.”

ZHIYUN CRANE 3 LAB: WE ARE WORKERS

When a project begins to reveal itself, I’m never certain where I’ll end up but I always start with a question.

Why do we work? Why do we seem to have an urge to create?

As a filmmaker, I get to look at questions from every angle. And even a skillful craftsman’s ability to create is affected by his choice of tools. And when my creative vision is on the line, I know which tools I’ll choose.

FOR MORE WRITING SAMPLES OR TO DISCUSS YOUR PROJECT, WRITE ME